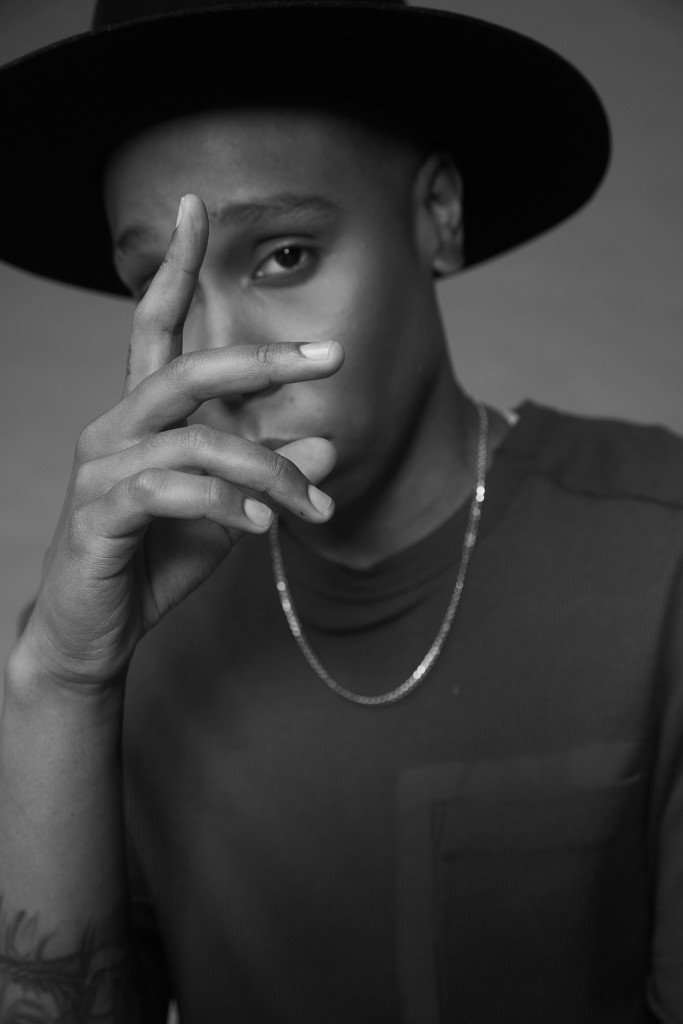

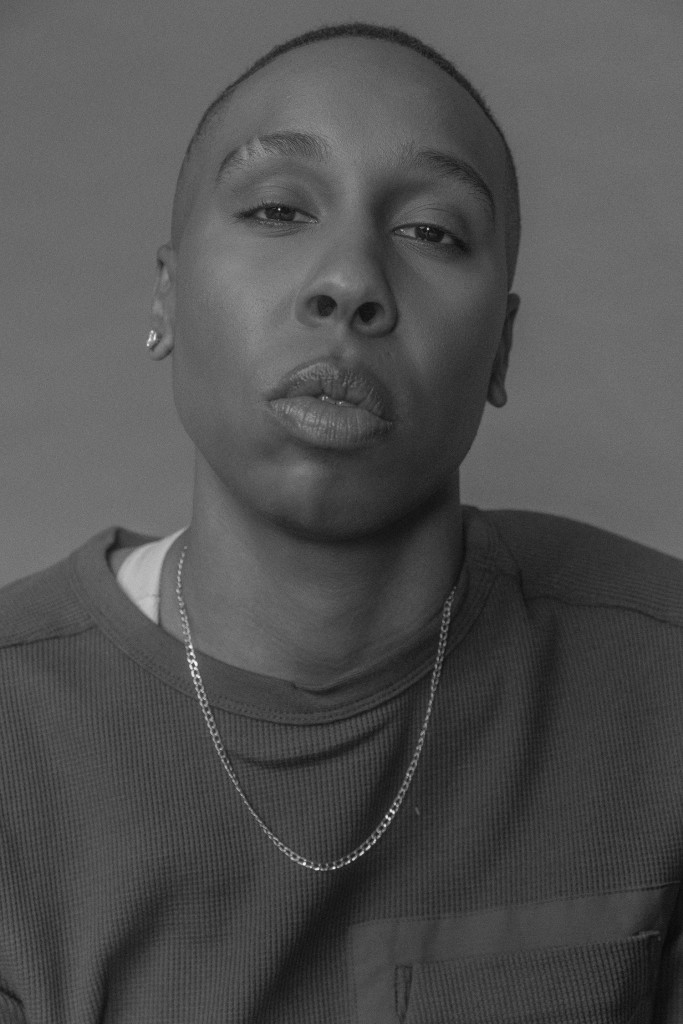

Being an out and proud woman is a revolutionary act, especially in Hollywood. For the writer, producer and actor, it’s a non-negotiable (with surprising dividends).

Lena Waithe has always paid attention to detail.

As a TV-obsessed child, she didn’t just admire celebrities, she needed to know everything about them: where they were born, which hobbies they loved, what motivated them. She would pore over their interviews, analyzing their answers. If she could manage to unwrap a corner of the glossy packaging and peek under it, she might catch a glimpse of someone flawed and complex. Someone truly interesting.

Excavating the human condition has worked out well for Waithe, and her curiosity has paid off for the rest of us, too. With sensitivity and flair, through her stories and characters, the writer, producer and actor captures what it means to be Black and queer in today’s America. Where we’d been reduced to harmful tropes, she’s contributed to making us whole again, showcasing the richness of our experiences, traumas and joys. This reconstruction work has earned Waithe best known for creating the drama The Chi and for her supporting turn in the comedy series Master of None—a coveted spot in Hollywood, critical acclaim and a keen LGBTQ+ following.

On the day of our interview, Waithe has turned her laser-focused attention to detail toward her clothing. An unabashed fashion plate, she serves a relentlessly stylish soft-stud aesthetic on red carpets and on social media. Her sneaker addiction is well documented in her Instagram stories; the now-legendary rainbow cape she wore at the 2018 Met Gala broke the Internet. Today, however, I can’t see her or what she’s wearing. She’s in Los Angeles, I’m in Toronto and we’re speaking over the phone. But as I soon learn, generosity is another of the 34-year-old’s qualities. To make up for our lack of face time, she’s meticulously describing her outfit.

The enumeration moves from the bottom up: off-white Nike Air Prestos (“the first edition, not the second”), black Nike stretch pants and a hoodie that reads “No More Comics in L.A.” sent to her by the creators of the web series after she donated seed money. She’s wearing a snapback emblazoned with the word “Treated,” Chicago slang for being schooled. “Oh, and under the hoodie, I have a shirt with a print on it,” she adds a few minutes later. It’s the way a character would be described in a script the first time we meet them—the details only a writer knows another writer would need.

*

Waithe’s parents divorced when she was three, and her mother moved her two daughters into their grandmother’s house in Chicago’s South Side, a neighbourhood Waithe would revisit more than two decades later in The Chi. The three generations of women lived there together for the next nine years. I ask Waithe what she was like as a child. Studious? Overachieving? Mischievous? “It was a combination of all of those, depending on the day,” she says. “I definitely wasn’t a saint. But I was also very curious. I could be obsessive about things.”

That was especially true of TV and film. Blockbuster card in hand, Waithe once tried to rent every title in the store and was known to watch the same movie—Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, say—for weeks at a time. By the age of seven, raised on A Different World, In Living Color and The Cosby Show, Waithe knew she wanted to be a TV writer. These shows, which brought gains in popular representation for Black people, impacted her significantly. “We got to see these really interesting dynamics of ourselves,” she says. “A lot of people my age didn’t just want to be professionals, they wanted to be great. They were proud of being Black. They were proud of being smart.”

__

__

Waithe is a fast talker, her mouth working double-time to keep up with her mind. Her voice has a warmth to it that in no way detracts from her readiness to tell it like it is. She is unapologetic about what she wants for herself and for the rest of the young, Black, queer creatives aspiring to be where she is. She’s set on changing the industry, and she’s clearing space to bring people in with her.

*

In January 2018, dressed in an all-black tux in support of the Time’s Up movement against sexual harassment, Waithe was walking the Golden Globes red carpet when her publicist told her she’d secured the cover of Vanity Fair. “I didn’t even know we were going for it, so I was blown away,” she recalls, laughing.

That April issue was also a baptism for Radhika Jones, the magazine’s new editor-in-chief and the first woman of colour to head up Condé Nast’s flagship publication. Jones opted for something and someone entirely new for the monthly: a Black lesbian in a plain white crew neck, sporting a double-strand chain necklace, minimal makeup and long dreadlocks slung over one shoulder. Her only other embellishment was a smirk. Gracing a magazine typically populated by white women in designer gowns, Waithe was an unabashed ambassador for a new Hollywood. Praise rolled in from across the industry, particularly from actors of colour such as Mindy Kaling, Gabrielle Union, Chadwick Boseman, Zendaya and Lupita Nyong’o. Their reactions were striking in their similarity: for so long, bodies like ours have been blocked from entering the mainstream; the face on the cover is a game-changer.

Being an out, Black woman in today’s America is a revolutionary act. As rights for women and LGBTQ+ folks are rolled back, and people of colour continue to be victims of state-sanctioned violence and the prison-industrial complex, more public figures are using their platform to speak out on issues related to race, gender and the lack of diverse representation. Is Waithe, a self-proclaimed “shit talker,” ever worried about being penalized for raising her voice? “No, I don’t believe in that,” she says. If she has an opportunity to make a speech or take a stand, she will. “It’s my responsibility. I don’t know how to hide.”

The past few years have shone a spotlight on race relations in a way not seen since the civil rights movement. Confronted with the growing number of deaths of Black men at the hands of police, people of colour have been speaking out about their pain (altercations with law enforcement, everyday microaggressions) and their joy (#BlackGirlMagic). At the same time, calls for greater and more realistic media representation have become more insistent. Whether it’s due to #OscarsSoWhite, the condemnation of whitewashing in lm and television or the rise in reporting about the lack of showrunners and writers of colour, the demands to be included are finally being heard—and, in some instances, even being met.

Black-led entertainment has begotten shows such as Scandal, How to Get Away With Murder, Empire, Queen Sugar, Insecure, Atlanta, Black-ish and Dear White People. Films are making history, with Moonlight winning Best Picture at the 2017 Academy Awards, Get Out snagging the 2018 Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and Black Panther smashing box-of ce records across North America.

__

__

“This is the kind of work most of us have wanted to make forever, but there’s definitely a shift that happened where now Black content is very much on trend,” Waithe says. “All these things with people of colour at the forefront struck a nerve with not just Black people, but with everybody,” she says. “So then all of a sudden Hollywood goes, ‘Oh, okay. We need our Black shit.’ I’m grateful for that, and I’m taking advantage of it.” So Waithe is leaping through the window of opportunity. Who can blame her? The most recent GLAAD report on representation in the media showed that although the number of LGBTQ+ characters on TV has increased, the number of queer people of colour has plummeted. Well, Waithe’s projects already include both—and more. She’s working at the intersections of race, gender, class and sexuality in ways that deviate sharply from the damaging tropes about blackness, queerness and womanhood that we’ve been forced to watch in the past.

Through her lens, there is a multiplicity of Black experiences. We are not one-dimensional spectacles to be consumed. By producing the film Dear White People, she highlighted the Black Ivy League. The Chi humanizes the places and people (especially Black men) so often painted as criminal by sensational headlines. Waithe’s own coming-out story, which she mined for the epic “Thanksgiving” episode of Master of None, netted her an Emmy for Comedy Writing, making her the first Black woman ever to receive the award.

And there’s so much more to come. Twenties, a show that Waithe wrote in 2009 about the lives of a queer Black woman and her two straight friends, finally got a pilot order earlier this year, and Universal is making Queen & Slim, a feature film Waithe wrote about a Black couple who kill a police officer in self-defence. Plus, she continues to make good on her promise to bring folks up with her: she’s the executive producer of both a dark comedy series about a gay Black man struggling with mental health and Them, a horror anthology about being Black in America. This isn’t just an impressive list of accomplishments—it’s a master class in capturing and crystallizing intricate realities.

Striking a balance between imagination and real life is what makes a great TV writer, according to Waithe. “I don’t drink alcohol; that’s a tidbit about me. And Slim [from Queen & Slim ] doesn’t drink.” One of The Chi’s young protagonists, Emmett, has an insatiable obsession with sneakers, like Waithe. Her fiancée Alana Mayo, a production executive, also creeps into her work. “The little dynamics between us will pop up. I think they always should,” she says. “If there aren’t pieces of you in your work, then it’s not going to be memorable.”

*

When Waithe walked into a room full of executives a couple of years ago to talk about The Chi, she already knew they were interested. She wouldn’t have taken the meeting if they weren’t. “I don’t like the word ‘pitch,’” she says. “I’m not pitching shit. I’m in there having a conversation.” It’s an enviable position. But at one time, Waithe was on the outside looking in—a fact she doesn’t easily forget. After arriving in Hollywood in 2006, she got a job assisting Love & Basketball director Gina Prince-Bythewood. Later, she moved on to become a production assistant for Ava DuVernay (Selma, A Wrinkle in Time). Now she’s giving back, a contribution that’s still sorely needed. According to a recent report by the advocacy organization Color of Change, two-thirds of 18 U.S. TV platforms in 2016–17 had zero black writers. By her count, Waithe has approximately 70 mentees, who take part in writing groups or work as her assistants. “I don’t ever want someone not to reach their full potential. I don’t ever want someone to go to their grave with a dream deferred,” she says. Still, her generosity doesn’t come for free—you better prove yourself. “I want to give people the tools and opportunities they need to tell stories, but I need them to work,” she says.

If writing, acting, producing, mentoring and advocating is a lot of labour, Waithe doesn’t seem to notice. Instead, she talks about all the people who help get everything done: her manager, along with a sizeable team of agents, assistants and interns. “I think people assume that because there are a lot of things going on, I’m working 24/7,” she says. She’s not, or not quite. Though she did “quickly” read three scripts the Sunday before we spoke, Waithe tries to keep her weekends work-free. To unwind, she gets massages, watches TV with Mayo and hangs out with friends. Waithe is no longer the child scouring the interviews of her favourite stars, eager for telling details. These days, she gets to write the people she wants to see. And she’s now the one being researched, though observers don’t need to dig deep to discover that Waithe is complex. It takes even less digging to see the groundswell of support behind her.

So why Waithe and not someone else? She’s not sure, but she has a theory: “Maybe because I’m giving out all love. I ain’t got no shit or no beef with anybody, and I don’t get it from anyone else. It’s just too much work to be dealing with that. I’m good.” A person with self-assurance, vision, grit, determination and a generous spirit—so many of the characteristics that make up a great leader—has penetrated the industry. She’s making films and shows about people who look like her and who share her experiences. She’s working with people like that, too, holding the door open and extending a hand. Hearkening back to the ’90s but with an eye on longevity, Black on-screen representation is being revived.

The next few years will be very busy for Waithe, but she knows there will come a time when her writing projects will slow down. She’s determined that it happen according to her schedule. She wants to build an empire, something to inspire young people of colour to pursue their own dreams of TV writing and producing. “I eventually just want to help people get their shit made. That’s ultimately my goal,” she says. “Because if there are more of us doing this—if all of us start to check if somebody’s got some shine—that’s how you change the business from the inside out.”

By Eternity Martis

Photos Kelly Jacob & Neldy Germain (The Woman Power)