My friend’s housewarming party starts in an hour, a February night during a Calgary cold snap. “What else can I help with?” I ask her, and that’s how I end up outside, shoving the lip of a shovel through knee-high snow atop iced-over sidewalk. I adjust my stance above the exposed swatch, grab the handle again hard with an eager grip inside neon yellow fleece: gloves my adoptive family gave me before I—and my Maple Leaf card—moved north. I try again against ice I know won’t give. The first twenty feet of sidewalk cleared, my hands burn. I head toward the steps that lead into the furnaced home, out of the Celsius 23-below.

Before I open the frosted screen door, I look back to the yard, half the job still waiting. In the town I come from, it could snow through April, but I left it a summer long ago; it’s been fifteen years since I’ve shovelled such heaps. My edges aren’t straight. The path between snowed-under yard and milky-iced sidewalk looks like a fabric ripped in haste, not clean or neighbourly lines. How will the mess of my effort look once the daylight returns? I know well how good intentions can soon be dubbed incorrect.

Worry slips into places the cold’s already reached. My body can’t absorb the house’s heat as I enter the kitchen. My friend’s got dish gloves on, working through our day’s dirtied glasses and plates. A fresh start to the night before the party begins. I laugh as I say it, but my next question is sincere. I ask if she’ll check my work.

I am not straight, and I come from a place that required me to be. An old home: facing others’ disgust until I began to wonder if it was truly deserved, that I really am that wrong. I come from a terrain that reserved the right to conditions, to casting out, to homophobia. It set my entire being on uncertain footing—taken in some places, pushed out others. Bracing: that black ice will find my feet, that safety comes from correctness, that expulsion waits along edges. That being helpful mitigates danger, earns my place. I’ve been welcomed by a new family, and by familial friends, and now a new country. But always at risk: will you keep me?

Here is a strategy to take the edge off that risk: in the face of rejection, let me be outstanding. Let me prove myself far beyond disownment. Let my deeds outpace the jeopardy. People asked me—when I filed papers, when the Maple Leaf card came— if I was running away. It’s a running toward, I’d tell them. I’m running toward something, I think. I thought. I thought there wasn’t fear in this choice, but here I am in Calgary, anxious over the zig zag I’ve shoveled.

Running away, running toward. Inside the kitchen, I shift my weight from one foot to the other. My friend turns off the faucet, looks at the hands I’m trying to rub back into feeling. “I’ll get back out there in a second,” I say, wiggling my fingers in the air. “Just need to warm these up a little first.”

“Oh, hon,” she says, picking up the first neon glove from its damp stack on the counter. “Don’t you have a pair of Hot Paws?” She fishes bulky black mittens from the foyer closet. Sliding them on, my hands become hands again: warm, human, capable. “We’ll get you some at Canadian Tire,” she says. She winks.

I point into the night. I worry over the sidewalk again, then realize I’m holding my breath. A phrase comes that I’ve never said before, knowing my position, my whiteness, my birth country passport. My privilege. Knowing nations aren’t monoliths, and no person is static, these words pop out: “I’m trying to be a good immigrant.”

She peeks through the cold sheen of the screen door window. She nods her head slowly as she assesses. “Doin’ great.” I zip my coat again, clap those Hot Paws together. Here goes. Twenty more feet—how many metres is that, anyway? The second half of sidewalk feels less menacing. Each time I heave the drift to the side, I understand differently the surface underneath: known, manageable, good enough.

No one slips along the walkway. They know how to handle ice and they know how to welcome, even if the occasion is another person’s housewarming. We share snacks, cheers plastic cups. I learn their names and kindnesses. I’m new in this space, but they bring me into the smooth curve of their circle, their warmth, their here.

My queerness cost me things that aren’t easily replaced. Can anyone ever truly start over when so much feels missing from the onset? Trauma is rupture. It covers the pathways, but tonight, as the heat works its way through, I’m realizing I will get better with a shovel. I won’t always get through the ice, and I can’t ever correct all the wronged. But this snow, this friend, her Hot Paws and her doin’ great, this deep relief of welcome, they give me hope for what’s ahead.

By Ellen Adams

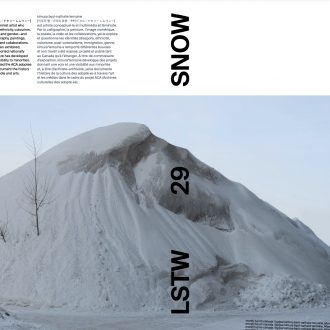

Photo by:

kimura byol-nathalie lemoine

(키무라 별 – 나타리 르뫈 – ビヨル – ナタリー レムワンー)

is a conceptual multimedia feminist artist who works on identities—diaspora, ethnicity, colourism, post-colonialism, immigration and gender—and expresses them through calligraphy, paintings, digital images, poems, videos and collaborations. kimura*lemoine’s work has been exhibited, screened, published and supported nationally and internationally. As curator, ze has developed projects that give voice and visibility to minorities. As an activist archivist, ze created the ACA adoptee cultural archives project to document the history of adoptee culture through media and arts.