Some cities and personas are synonymous with social and cultural moments: Sid Vicious and Punk Rock with 70s England, Seattle with Grunge and Kurt Cobain with the 90s. Others, however, have been given less due. In the 1980s, Toronto birthed queercore. The genre is an experimental, DIY movement of self-proclaimed dykes, fags and trans artists, who worked across all mediums to express and see themselves in print, on-screen, and on stage, the way they wanted to be seen.

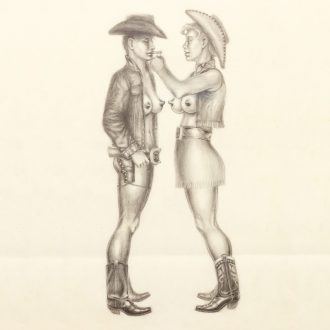

Multi-faceted Canadian artist G.B. Jones was the mother of queercore. In 1985, she co-created the zine JDs with collaborator Bruce la Bruce. The publication was the precursor to so many others, with its cheeky polemics and manifestos like Don’t Be Gay. The magazine also published queer, feminist artwork such as Tom Girl, GB’s erotic lesbian take on Tom of Finland. As for the acronym, it stood for Juvenile Delinquents at times, and at others, for JD Salinger, Jeffrey Dahmer, or James Dean.

That same year, Jones’s all-women band Fifth Column released their debut LP, To Sir With Hate, which has since been shortlisted for the Polaris Music Prize. Through touring, cassette trading, and underground community-building G.B. Jones connected with other female and queer artists who were looking to make themselves visible – at least to each other. Jones started casting and collaborating with friends on Super 8 films like The Yo-Yo Gang, a lo-fi exploitation film about a group of feminist punk dykes causing trouble on the streets of Toronto.

“It was all about self-representation versus the media’s type of representation of queer people and how we wanted to it take back,” Jones says.

“Basically, we just wanted to use any medium we could.”

Almost 40 years later, Jones is still making queer music, film, and art in Toronto. Her new band Opera Arcana (a duo with Minus Smile of Kids on TV) composes dark, ethereal, esoteric soundtracks for films that have trouble finding distribution, even at LGBTQ film festivals where experimental queer filmmakers first found their audiences. This year, Opera Arcana is releasing two new soundtracks, an EP, and Jones is remastering Fifth Column‘s album, which only ever released 500 copies. While times have changed, she hasn’t – at least not when it comes to making experimental and explicitly queer art.

“Queer people should have their own culture,” Jones says. “We need to recreate the kind of communities that we had in the 80’s. It seems like we need to always keep recreating them over and over again. You have to work to keep it all alive.”

__

*G.B. Jones – Untitled – 1997 / Graphite on paper 11.8 x 9.1 in (30 x 23 cm) – Courtesy of G.B. Jones and Cooper Cole, Toronto

__

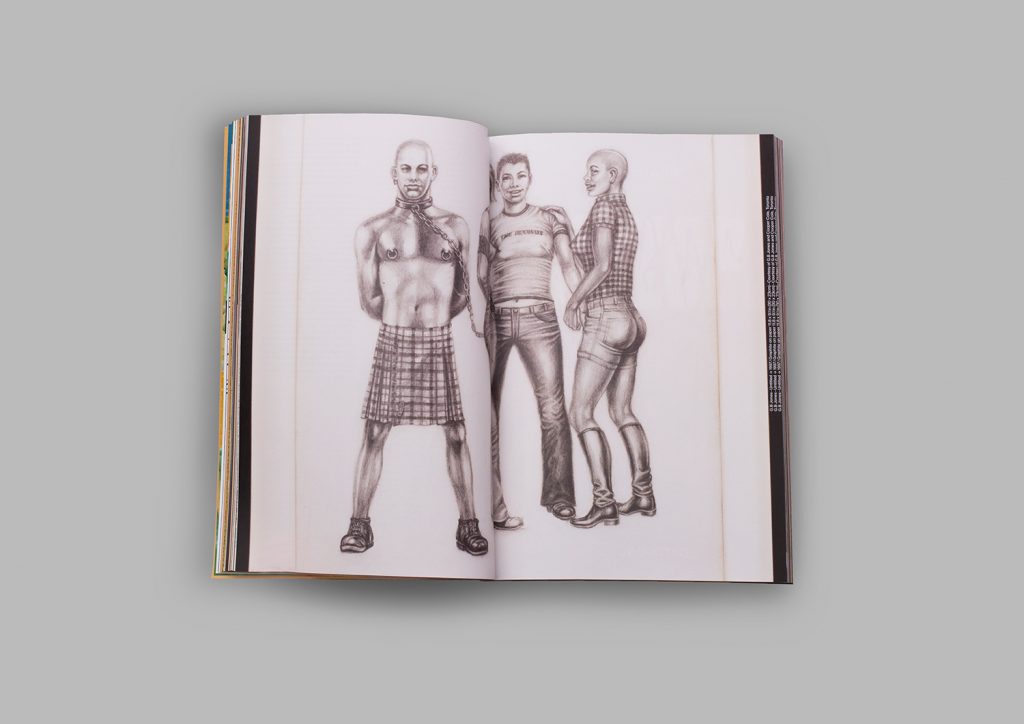

Jones is relentlessly putting in the work. She’s currently showing work at Toronto-based gallery Cooper Cole and was recently published in A Queer Anthology of Sickness published by UK based Pilot Press in 2017. In the last 10 years, she’s appeared in two documentaries about her contributions, donning her signature look of back-length wavy red hair, pale skin, and a pair of opaque black sunglasses to match her all-black ensemble. Jones appears in She Said Boom: The Story of Fifth Column, where she tells all about the beginnings of queercore, Fifth Column’s tours with the likes of Team Dresch, their released singles on seminal American labels K Records and Kill Rock Stars before officially disbanding in 2002. In the documentary Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution (2017), director Yony Leyser traces the lineage of queer pop, rock, and post-punk back to Jones and La Bruce’s partnership. In the film, Kathleen Hanna, Beth Ditto, John Waters, Kim Gordon, and Hole’s Patty Schemel speak on queercore’s lost legacy and the generations of art it inspired — including riot grrrl.

“I think homophobia did have some effect in the telling of the riot grrrl story,” Jones says. “Because for me, I see it as being really interconnected with queercore. And I think most of the women that were actually involved in creating riot grrrl — well I know for a fact, that they saw it as a being descendent of queercore.”

However, like most of the women who were part of the now commodified and corporatized riot grrrl, Jones has never been interested in the kinds of attention other artists might crave. She works intending to be accessible only to queers, punks, and women like her. With every medium, she is still experimenting something she sees as the queer artist’s aesthetic — living as an outsider who defines themselves instead of reacting to influences of the mainstream.

“I think there’s a lot of queer people, just like people in all sorts of different subcultures and minorities, that desperately want mainstream attention and validation. And if they don’t get that validation, they feel like they’ve been ignored and left out,” Jones says. “And rather than just feel that way, I just think, ‘Why not just create your own thing and forget about being validated by the mainstream? Because their validation really just means you are exploitation. That’s what it comes down to, I think.”

By Trish Bendix